Thermos informationsheet

Thermos information for tutors and student counselors

Dear student counselor,

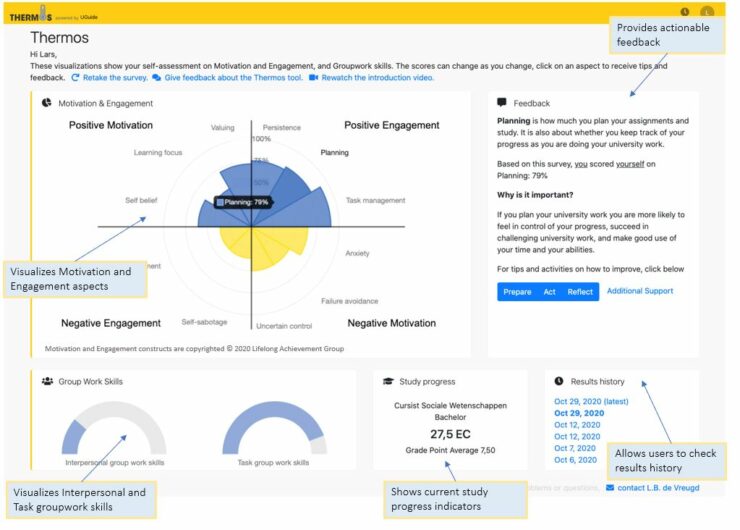

This document explains the different parts of the Thermos-dashboard, to help you provide students with better support and guidance. In the tool, students’ fill out a questionnaire focused on their Motivation and Engagement and their groupwork skills. Students’ responses to the survey are presented in several visualizations in the dashboard:

When talking to students in regard to their personal dashboard, keep in mind and remind them:

- All aspects in the dashboard are learnable and changeable.

- If scores in the dashboard are not great, this doesn’t mean this is a ‘bad’ student.

- Don’t focus solely on the negatives in the dashboard – high positive scores are strengths which can be used throughout a study program.

- Even high-achieving students could benefit from reducing negative aspects, this is not uncommon.

- The survey is not a clinical diagnostic or clinical intervention tool – other materials or clinically trained professionals are needed for those purposes.

- You don’t need to be an expert in all the aspects of the dashboard. Referring to the exercises and/or additional support and supporting that process is helpful too.

- Don’t ask students about specific scores in the dashboard (e.g. ‘What was your score on planning?’) as this is a student’s personal data. Give students some room so they can decide what to reflect upon (e.g. ‘What stood out for you in your dashboard?’ or ‘Did you recognize yourself in the visualizations?’)

- Try to find a balance when it comes to responsibility – students may need support or guidance, but should also be in the driver’s seat when it comes to their study.

-

suggestions based partially on the Testing and Administration Guidelines, © 2016 Lifelong Achievement Group (visit www.lifelongachievement.com for Terms and Conditions)

These are the different parts of the dashboard:

Positive Motivation is the collective term for thoughts that can lead to positive engagement with the study program. It reflects helpful thoughts of students when studying at university. Higher scores on positive motivation on the dashboard are therefore desirable. Positive motivation consists of three parts:

Self-belief regards students’ beliefs and confidence in their ability to succeed in university, to meet the study challenges, to utilize learning opportunities, and to perform to the best of their ability in their study. If students have positive self-belief, they tend to take on difficult study tasks confidently, feel optimistic, try hard, and enjoy university more.

- Learning focus is the extent to which students are focused on learning, solving problems, and developing skills. It’s also about whether they feel successful and gain satisfaction in mastering what they want to achieve. If students’ learning focus increases, they tend to enjoy learning more, enjoy challenges, and study for their own satisfaction instead of studying for rewards.

- Valuing is how much students believe what they learn at university is useful, important, and relevant to them or the world in general. If students’ value university, they tend to be interested in what they learn, persist when study tasks or assignments get difficult, and enjoy university.

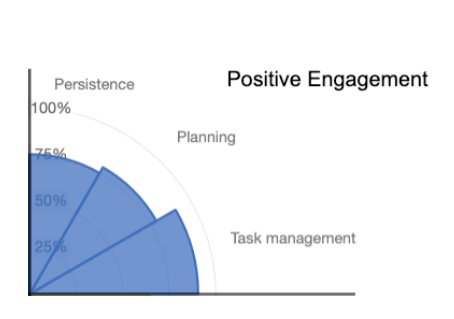

Positive engagement is the study behavior that comes from positive motivation. These behaviors are helpful for students when studying at university. For positive engagement, higher scores are desirable.

Positive engagement consists of three parts:

- Persistence is how long and how hard students keep trying to understand a problem and come to a solution even when that problem is difficult or challenging. If students are persistent, they tend to achieve what they set out to do more often, be more motivated to succeed, and be good at problem solving.

- Planning is how much students plan their assignments and study. It is also about whether they keep track of their progress as they are studying. If students engage in planning, they are more likely to feel in control of their progress, succeed in challenging university work, and make good use of their time and abilities.

- Task management is the way students use their study time, organize their study timetable, and choose and arrange where they study. If students manage their study well, they tend to be more efficient. This can be done by studying in places where they can concentrate, using their study time well without getting distracted, and sticking to a study timetable.

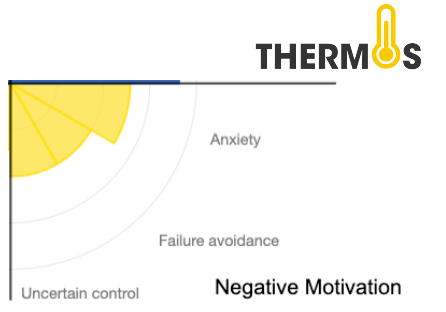

Negative Motivation are thoughts that can lead to negative engagement. These thoughts can hinder students when studying at university. Here, lower scores are desirable. Negative motivation consists of three parts:

- Anxiety has two aspects: feeling nervous and worrying. Feeling nervous is the uneasy or sick feeling a student gets when they think about their university work, assignments, or exams. Worrying is their fear about not doing very well in their university work, assignments, or exams. A bit of anxiety can be helpful, but too much can hinder students in their study. Overcoming anxiety may lead to an easier time concentrating or remembering things.

- Failure avoidance is when students do their university work mainly to avoid doing poorly, rather than to aim for success or improvement. Or that students avoid being seen as doing poorly. If students can overcome failure avoidance, they tend to no longer fear failure, feel pessimistic, or feel anxious when thinking about or doing their university work.

- Uncertain control is when students are unsure about how to do well or how to avoid doing poorly. If a student is uncertain about the control they have over their study, they can feel somewhat helpless when doing their university work, fear failure, or have negative thoughts about their university work.

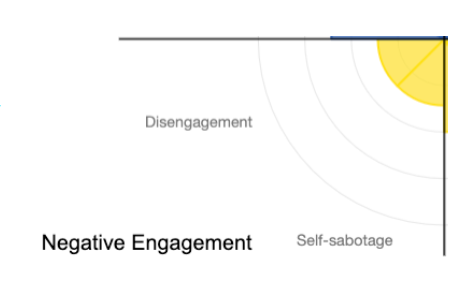

Negative engagement is the behavior that comes from negative motivation. These behaviors can hinder students in their study. For negative engagement, lower scores are desirable. Negative engagement consists of two parts:

- Self-sabotage is when students do things that reduce their success at university, e.g. procrastinating or wasting time when they are meant to be studying for an exam. If students overcome their self-sabotage, they tend to make the most of their ability, and feel good about studying at university.

- Disengagement is giving up on a particular university subject or studying in general. If students can overcome their disengagement, they are more likely to believe there is something they can do to avoid failure or repeat or attain success. They also become more interested in university or university work.

Note: The Motivation and Engagement Wheel and its different aspects are copyright © 2020 Lifelong Achievement Group

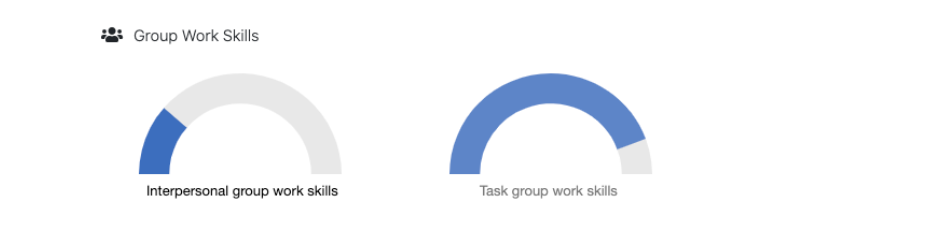

Group work skills are the skills students need to effectively collaborate. When studying at university, students often work in groups. Collaboration can be powerful to enhance students’ academic achievement, self-esteem, attitude towards learning activities, and retention. However, just placing students in a group can have adverse effects, when for example interpersonal conflict or social loafing arises. Higher scores on group work skills are therefore desirable. Groupwork skills in the Thermos- dashboard consist of two parts:

- Interpersonal group work skills are those skills necessary for working with others, e.g. effectively resolving conflict, understanding information exchange networks, and providing social support. Advanced interpersonal group work skills will improve the experience of working with other students, through positive and supportive social interactions and enhanced communication.

- Task group work skills are those skills necessary for the successful completion of group assignments, e.g. establishing goals, planning and sequencing activities, or coordinating group interdependencies. Advanced task group work skills will likely improve the experience of working with other students, through the efficient use of time and productive meetings. As well as, reducing social loafing (‘free-riding’ or ‘meeliften’).

Further reading:

To learn more about Groupwork skills:

Cumming, J., Woodcock, C., Cooley, S. J., Holland, M. J., & Burns, V. E. (2015). Development and validation of the groupwork skills questionnaire (GSQ) for higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(7), 988-1001.

To learn more about the Motivation and Engagement Wheel:

Martin, A. J. (2007). Examining a multidimensional model of student motivation and engagement using a construct validation approach. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 413-440.

To learn more about feedback types and processes:

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of educational research, 77(1), 81 – 112.

To learn more about Learning Analytics Dashboards and implementation processes:

Jivet, I., Scheffel, M., Specht, M., & Drachsler, H. (2018, March). License to evaluate: Preparing learning analytics dashboards for educational practice. In Proceedings of the 8th international conference on learning analytics and knowledge (pp. 31-40).

Lang, C., Siemens, G., Wise, A., & Gasevic, D. (Eds.). (2017). Handbook of learning analytics. SOLAR, Society for Learning Analytics and Research. DOI: 10.18608/hla17

Wise, A. F., Vytasek, J. M., Hausknecht, S., & Zhao, Y. (2016). Developing Learning Analytics Design Knowledge in the” Middle Space”: The Student Tuning Model and Align Design Framework for Learning Analytics Use. Online Learning, 20(2), 155-182.

For further questions, feel free to get in touch with Lars de Vreugd (projectmanager) at L.b.devreugd- 2@umcutrecht.nl